As many provinces and territories struggle with health worker shortages and overcrowded emergency departments, politicians are turning to financial incentives to keep or hire staff.

In the past seven months, at least five provinces have announced tens of thousands in retention bonuses or other recruiting benefits to keep or attract doctors and nurses.

But is financial compensation the right recruitment tool?

Some researchers and recruiters say, based on studies and their own experience, that one-time financial incentives aren’t effective enough to keep healthcare workers on the job.

“Financial incentives have always been, and will continue to be, Band-Aids,” said Maria Mathews, a professor in the department of family medicine at Western University in London, Ont.

Nurses’ unions and national health leaders have said financial incentives are just one piece of the puzzle needed to fix the current strain on health care.

Working conditions, wages and long hours are things that need to be addressed, they have said.

“What’s important to these doctors and nurses? In 2022, it’s quality of life,” said David Este, professor emeritus of social work at the University of Calgary, who has studied the issue.

“If they are working in chronically understaffed hospitals … and those working conditions are maintained over a long period, I don’t think financial incentives have the ability to deal with the nature of a working environment.”

Why financial incentives are the solution

Provincial and territorial governments have relied on financial incentives for decades, they said a 2015 study which Mathews co-authored. These incentives vary from province to province, and also vary depending on the specific role and need of the area.

Ontario, Alberta, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia and PEI are the most recent provinces to announce some form of financial compensation for new or existing family physicians or nurse practitioners.

Health workers who quit in droves due to the system plague burnout and understaffing

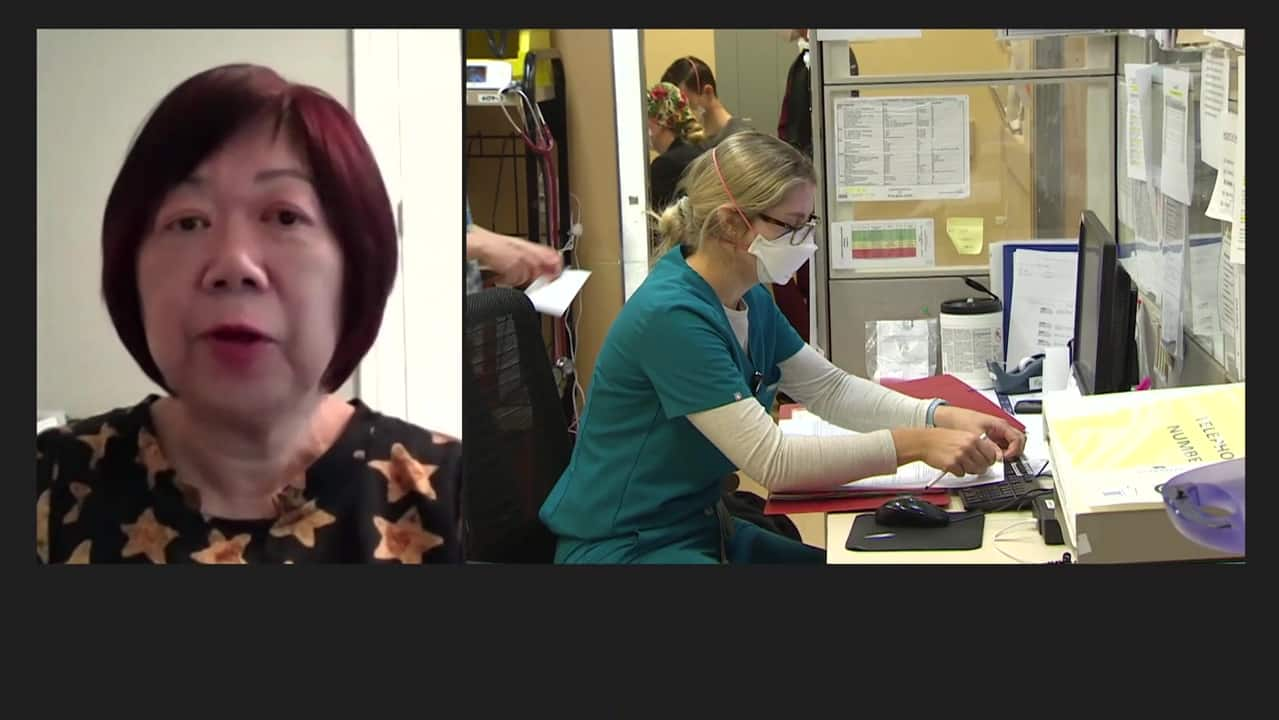

Canada’s struggling health care system now faces funding and staffing challenges that threaten the entire sector. Exhausted and overworked nurses are quitting in droves, while jurisdictions struggle to convince them to stay. Healthcare workers share the changes they say will help them continue.

It’s a move Mathews has seen many times before, adding that politicians turn to financial incentives because they can be delivered relatively quickly.

“The problem will not be solved just by giving people financial incentives. Because if that were the case, we wouldn’t be losing nurses,” added Este.

And there are notable differences between the compensation initiatives recently announced by provincial governments and those funded by taxpayers.

Earlier this month, Registered Nurses’ Union NL president Yvette Coffey and Newfoundland and Labrador Premier Andrew Furey announced new measures aimed at retaining nurses. (Ted Dillon/CBC)

Earlier this month, Registered Nurses’ Union NL president Yvette Coffey and Newfoundland and Labrador Premier Andrew Furey announced new measures aimed at retaining nurses. (Ted Dillon/CBC)

Ontario and Newfoundland and Labrador retention bonuses for nurses announced to keep existing staff. This differs from the recently announced new money for family doctors moving to rural communities AlbertaPEI and Nova Scotia.

“I think the governments, both provincially and federally, are looking for an immediate solution because the need is immediate,” said Dr. Vesta Michelle Warren, president of the Alberta Medical Association and a family physician in Sundre, Alta.

Can financial incentives help?

There are many reasons why hospitals feel extra strain, causing them to close or forcing patients to wait hours. Experts have said one of those reasons is that people without a family doctor are adding to the long waits at hospitals across the country.

Last month, about 25 per cent of patients who came to the emergency rooms at Richmond Hill and Cortellucci Vaughan hospitals in north Toronto did not have a family doctor, according to Dr. David Rauchwerger, medical director of the department of Mackenzie Health Emergencies.

That’s much higher than the five percent figure before the pandemic, he said.

Providing a better work-life balance and helping employees feel connected to communities often rank higher for healthcare professionals when deciding whether to stay or leave, they found studies across Canada. (Nathan Denette/The Canadian Press)

Politicians in Alberta and Nova Scotia hope their newly announced bonuses and other recruitment efforts will attract doctors and specialists to work in predominantly rural or underserved areas. PEI officials expanded their incentives to include family physicians or some specialists who accept jobs anywhere in the province.

In studies conducted in Canada since the 1990s, hiring bonuses are often said not to be as important as other areas, such as working conditions and community amenities, to doctors.

Researchers who conducted a 2019 to study on retention interviewed 91 Alberta physicians, administrators, community members, and spouses, and found that health professionals rated financial incentives as “moderately important” for recruitment and not at all important for retaining a physician a community

Almost five million Canadians do not have a family doctor. This is one of the factors that contribute to stress in emergency rooms. (David Donnelly/Radio-Canada)

Almost five million Canadians do not have a family doctor. This is one of the factors that contribute to stress in emergency rooms. (David Donnelly/Radio-Canada)

In contrast, community members rated incentives highly for attracting physicians.

This echoes the findings of a 1999 studywhich said that despite “widespread deployment”, there is little evidence that funding-based approaches are particularly effective.

Another common practice in many provinces and territories is what is known as a return-of-service agreement or grant, which is typically offered to new graduates or internationally trained doctors to help offset some of their training or other costs, depending the experts

That’s often when a person signs an agreement to go work in a community for one to three years in most provinces, Mathews said.

She is looked Newfoundland and Labrador Return to Service Agreement data and says these agreements can bring people into underserved areas, but the agreements don’t “keep people in those communities.”

Sant Joan morning show7:30 p.mAnother doctor on how governments’ recruitment efforts have fallen short

The provincial government is now taking a big seduction approach to recruiting doctors to the province, but one doctor says it hasn’t been enough to bring him home. Let’s listen to Dr. Travis Barron and the Minister of Health.

In some cases, doctors paid with their contracts to leave the community. This is another team of researchers found happened in 1999 in other provinces such as Saskatchewan and Quebec.

“Financial incentives will only go so far in recruiting and retaining people,” Mathews said.

Getting doctors and other health care workers to stay in the community is something Mayor Craig Copeland in Cold Lake, Alta., knows well.

Since he was elected in 2007, the community in northeast Edmonton has struggled to recruit doctors to the area. The area has needed five to six doctors for several years, he said.

To bring them into the community, the city is currently offering $20,000 and paying the interest on a $50,000 line of credit for the doctors if they agree to work in Cold Lake.

“You have to pay to play, unfortunately,” Copeland said.

Access to data on financial incentives and retention programs should be better shared with academics and those studying the topic, Mathews said, as it is quite limited.

Bryan MacLean, who recruits doctors for the University of Saskatchewan’s Northern Medical Services and has been a recruiter for years, said he and his colleagues are trying to collect this “hard-wired” information about recruitment and retention programs because better access to data.

But from what he has seen, doctors will work in a community, fulfill their commitment to service, and then move on.

“There needs to be more emphasis on retention issues by the government,” he said.

Dr. Vesta Michelle Warren is the president of the Alberta Medical Association. She says it wasn’t the signing bonus that kept her in Sundre, Alta., but the community lifestyle and working conditions. (Alberta Medical Association)

Dr. Vesta Michelle Warren is the president of the Alberta Medical Association. She says it wasn’t the signing bonus that kept her in Sundre, Alta., but the community lifestyle and working conditions. (Alberta Medical Association)

Warren said bonuses can help. But the president of the Alberta Medical Association said she and other colleagues often value other factors more, such as fitting into the community, whether their spouse can find work and whether they have a good work environment and a good team.

“I stayed at a center not because of this three-year bonus, but because it was very good for my family, for my kids, for me professionally,” Warren said of his return contract from the signed service in 1999.

Ontario nurses echoed a similar statement after the Ford government announced the $5,000 bonus earlier this year. Many nurses and union representatives said it won’t be enough to keep them on the job.

Foreign-educated nurse provides credentialing counseling to newcomers

Health care workers planning to come to Canada can better take advantage of pre-arrival services and start the accreditation process before arriving in this country, says Queenie Choo, a former nurse who trained in the UK and now heads an organization that helps newcomers.

“As long as you promise to do so [$5,000] for nurses, what they really want is support to do their job well and to do it safely,” read a joint letter submitted by four unions at the time.

The other solutions

Healthcare leaders, nurses and doctors have called for specific changes to address what happens in hospitals, clinics and family doctors’ offices.

Getting more health care workers, whether family doctors, nurses or other workers, is essential, many said.

MacLean and Warren agree that bringing in more physician assistants or nurse practitioners could create more team-based care.

Warren also said looking at bringing back Canadian students who trained at international medical schools is another option.

And if governments are serious about retention bonuses, Mathews said they should also offer them to other healthcare workers.

“If we don’t have the employees and if we don’t have good lab technicians, we can’t provide care,” he said.

[ad_2]

Source link