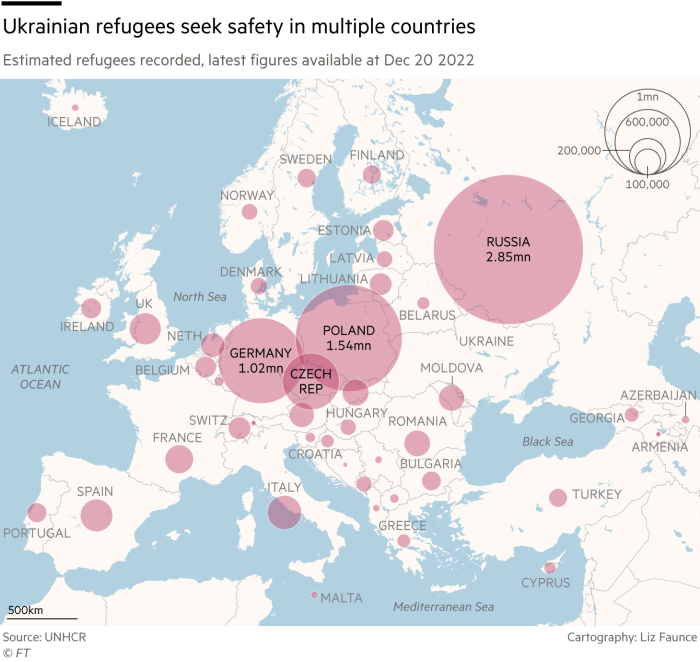

As millions of refugees flooded its border following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Poland was hailed as a role model. Almost overnight, its citizens formed an army of grassroots volunteers to help the displaced, donating money and welcoming Ukrainians into their homes.

There has been a slowdown in arrivals since the February 24 invasion, but the need remains acute, and the flow of assistance is drying up, with humanitarian activists saying “refugee fatigue” has consolidated

“It’s becoming very difficult to reach new people with the message that they should come and help Ukrainians,” said Jakub Tasiemski, lead coordinator of the Heart for animals Foundation based in the Polish capital Warsaw, which provides food and equipment for refugees’ pets. “Now we have a shortage of volunteers.”

In the city of Lublin, the lack of new funding has forced another Polish foundation, Skakanka, to close a warehouse where it stored food and clothes for refugees.

“Ukrainians are still calling and asking for help, but we are helpless because we have no money to replenish the supplies,” said the president of the foundation, Tamara Rutkowska.

Jakub Tasiemski says the regional government has stopped funding his charity, which provides food and equipment for refugees’ pets © Maciek Jazwiecki/FT

In the weeks immediately following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, 51 percent of Polish adults bought items for refugees, according to a survey released in July by the Polish Economic Institute, a think tank funded by been But within two months, the proportion doing so fell to 39%, while those giving cash donations dropped to 33% from 46% previously.

However, Poles gave almost 10 billion zlotys ($2 billion) to help Ukrainians between late February and late June, surpassing their charitable contributions for all of 2021, the survey found. He attributed the most recent decline to factors ranging from “moral exhaustion” to a sense that, as refugees settled, they needed less help.

The decline in support comes as Polish households face economic headwinds. The country has one of the highest inflation rates in Europe, at 15.6% in July, caused in part by the war in Ukraine.

Activists also say interest is waning because many Ukrainians have recently returned to the safer western half of their country, altering how Poles perceive the situation across the border.

Ukrainian volunteer Irina Mishyna says newcomers to her country often need more help than those who came before © Maciek Jazwiecki/FT

Ukrainian volunteer Irina Mishyna says newcomers to her country often need more help than those who came before © Maciek Jazwiecki/FT

“Everyone knows that there are fewer refugees now, but people should also know that those arriving often need more help than before, because they come from eastern cities that have been destroyed and occupied by the Russians,” said Irina Mishyna , Ukrainian volunteer who escaped to Warsaw with her 5-year-old son.

The Polish authorities have also ended some subsidies for refugees. Ukrainians can no longer travel for free on public transport in Warsaw, while last month the government scrapped a subsidy for Poles hosting Ukrainians worth 40 zlotys a day for each person helped. Government officials have stressed that the housing subsidy scheme was never meant to be extended beyond an emergency response.

Still, Tasiemski said the regional government had also stopped funding Heart for Animals. “If you ask me again in a week if we have enough dog and cat food, we’ll probably have run out,” he said.

Meanwhile, as in other nations hosting large numbers of displaced people, the relationship between refugees and their hosts has become more ambivalent.

American volunteer Hannah Ballew says locals in Warsaw are equally divided between those committed to helping refugees and those who want them to leave © Maciek Jazwiecki/FT

American volunteer Hannah Ballew says locals in Warsaw are equally divided between those committed to helping refugees and those who want them to leave © Maciek Jazwiecki/FT

Hannah Ballew, an American who traveled to Warsaw in April to work serving food to refugees, said: “If I look at the people around me, it’s a 50-50 situation, between those who are still very committed to helping Ukrainians and those I would just like to get out.”

The massive influx of Ukrainians into Warsaw since February has also pushed up rents. Online real estate search engine Otodom reported that in June average rental prices for apartments in the capital were around 24-32 percent higher than the same month last year. But recently some Polish landlords have started vetoing Ukrainian tenants, worried they will leave without notice, according to local real estate agents. In some cases, “the apartments are in ruins and the tenants are nowhere to be found,” said Milena Piotrowska, a Warsaw-based real estate agent.

Others are upset by what they see as the preferential treatment given to Ukrainians. Kamil Wasilowski, 38, queuing at a soup kitchen in central Warsaw that serves the homeless, said: “Ukrainians can come here whenever they want, while we can’t go to their special soup kitchens, they have apartments while we sleep in street, so of course that’s unfair.”

Konstantin Kisieliov, a 46-year-old Ukrainian, has found a part-time job as a courier in Warsaw and lives with his wife and three children in a flat provided for free by the Poles. But he senses a change in attitude among his hosts as the situation drags on. “We haven’t been told to leave yet, but we’re afraid that might be the case,” he said.

However, the government has emphasized the benefits for the country of hosting Ukrainians, many of whom are highly qualified. “The work of Ukrainians living in Poland can be a great added value for our economy,” Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki said in an interview in May with the Gazeta Polska newspaper.

recommended

Analysts also note that Poland’s far-right politicians, led by the Konfederacja party, have so far failed to stir up hostility or gain support for claims that refugees are being prioritized over locals. And Piotr Arak, director of the Polish Economic Institute, said that the Poles were grateful to the Ukrainians. “Compared to other Western Europeans, Poles still know that Ukrainians are really fighting our war,” he said.

Refugee fatigue was “absolutely normal because people get very tired after helping for many months,” said Maciej Duszczyk, a migration expert and professor at the University of Warsaw.

Despite the drop in support, Duszczyk stressed that Poland’s embrace of refugees had been unprecedented. He estimates that in the two weeks after the Russian invasion, 600,000 Polish households took in Ukrainians even before government subsidies were offered.

“I’ve looked at dozens of refugee crises around the world, and frankly, I think the Polish response should go down in the history books,” he said.

[ad_2]

Source link