Ireland’s three main banks face a ‘once-in-a-generation’ opportunity to expand as two of their rivals prepare to exit the market, leaving behind €30bn in loan books and 1 million customers.

Rising interest rates and the opportunity to grow at a fast pace provide optimism for the country’s banking system, which has been rehabilitated from a crisis more than a decade ago that crashed the entire economy irish

“For the first time in a number of years, we are seeing the green shoots of net new lending in Ireland, something that has threatened to come and never quite came,” said Bank of Ireland Chief Financial Officer Mark Spain . the country’s largest lender, he told the Financial Times.

But while bankers celebrate, others are increasingly concerned that the market has consolidated too quickly, with the exit of Ulster Bank and KBC potentially leading to an unhealthy reduction in the number of choices for customers.

In response to a government review of the industry, the Central Bank of Ireland said the country was in a “position where consolidation has led to growing concerns about market concentration and competition”.

Brian Lucey, professor of international finance at Trinity College’s business school, said Ireland was “entering an almost oligopolistic market” in retail banking. He said that while this would increase profits for the benefit of shareholders, it was “probably not” positive for consumers or the wider Irish economy.

Like many banks in Europe, the three remaining lenders in Ireland have benefited from rising interest rates and appeared upbeat in their half-year results in recent weeks.

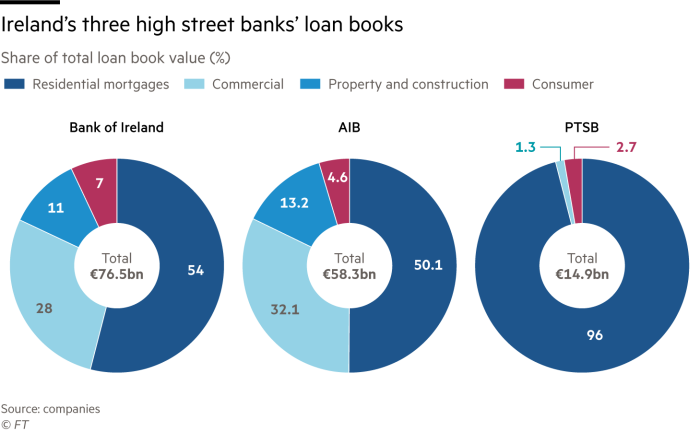

State-backed AIB reported a 74% rise in profits on higher revenue. BoI said it expected the state to withdraw as a shareholder this summer. Permanent TSB, which is also backed by the government, reported an increase in lending and expects to return to profit this year.

But Irish banks could have an edge over their European rivals. Brian Hayes, chief executive of the Banking and Payments Federation of Ireland, the industry’s leading voice, said 80% of its revenue was generated from interest rate movements, while 20% came from the commissions That compares with a 60-40 split in the EU, he said.

As inflation continues to rise, more rate hikes are on the cards. The European Central Bank raised rates in July by half a percentage point to zero, the first increase in 11 years, following in the footsteps of the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England.

The BoI said it expected €435 million in additional net interest income if rates rise by 1 percentage point, while AIB has targeted an increase of €369 million, based on its forecast models.

“When you look at 2023, there is clearly a very large and significant upside in interest income,” said Diarmaid Sheridan, banking analyst at exchange Davy.

“There are some inflationary impacts on costs, but much less than what you’re seeing on the revenue side,” he said. “It’s a very positive story. We have a bigger advantage [than EU banks] and we’re probably better insulated from some of the downside.”

Retail banks’ balance sheets have also been cleaned up since the crisis. A deluge of mortgage loans during Ireland’s “Celtic Tiger” boom, what Hayes calls the “crazy years”, brought banks to the brink of insolvency and forced Dublin to accept a £67.5bn bailout. EU and IMF euros.

As a result of their recklessness in the past, Irish banks must now apply strict controls to mortgage lending. The average loan-to-deposit ratio has fallen to 78% in 2020, from 102% in 2016. according to the Central Bank of Ireland. This is significantly lower than the EU bank average of 107%.

As the market contracts, PTSB in particular is poised to benefit from the industry’s dramatic restructuring.

PTSB is buying €7bn of mortgages from Ulster Bank, 25 of its branches and around €600,000 in assets from its asset and small business finance divisions. The deal will increase PTSB’s mortgage business by 40 percent, its small business book by 200 percent and its branch network by nearly a third.

“The transformation of the Ulster Bank deal for us is much more substantial than, say, AIB or Bank [of Ireland],” PTSB chief executive Eamonn Crowley told the FT. “It’s more incremental for them. For us, it’s a substantial change in both our balance sheet and our profitability, and indeed our ability to compete.”

BoI is buying 9 billion euros of residential mortgages from KBC and more than 4 billion euros of deposits, which it said would also increase its mortgage lending by 40 percent. AIB is buying €5.7bn of Ulster Bank mortgages and €3.7bn of commercial loans.

Despite the growth opportunities, political risk remains a headwind. Sinn Féin, the nationalist party in first place to win the next election due in 2025, has suggested it does not want the state to exit the banking sector entirely. This has fueled nervousness in some parts of the financial sector about public policy if the populist party takes power.

Pearse Doherty, Sinn Féin’s finance spokesman, criticized an abortive decision by AIB to withdraw cash services from 70 of its branches, saying if the state allowed full privatization “there will be no leverage that we can have… about other decisions they may have in the future”.

As banks emerge from state ownership, they are also looking to remove wage restrictions, one of the last vestiges of the financial crisis.

BoI is preparing to roll back executive pay caps and a ban on bonuses as the state sells its remaining stake, which has fallen to less than 3%.

Critics of the pay policy argue that it has led to a reduction in senior executives at Irish banks, while lenders in other countries, such as the US, can offer more competitive pay packages. BoI chief executive Francesca McDonagh will be the latest in a series of departures for senior Irish bankers when she leaves next month.

After more than a decade of Irish banks paying their dues and as the outlook for higher profits improves, Spain’s BoI said now was the time to lower payout limits, at least when its bank returns entirely in private hands.

“Restrictions must be removed for BoI,” he said. “I think we should be rewarded.”

[ad_2]

Source link