European lenders have endured a painful decade waiting for interest rates to rise.

But just as central banks are finally starting to move, the expected windfall is threatened by the looming recession and fears that cash-strapped governments could hit lenders with new taxes.

Last week, the European Central Bank raised interest rates for the first time since September 2011, half a percentage point to zero. This followed more aggressive hikes by the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England in attempts to control inflation that is expected to soon reach double digits.

“The world will have to relearn banking,” UBS chief executive Ralph Hamers told the Financial Times. “The euro zone has been in negative territory for eight years, Switzerland has been in negative territory for seven years, where people did not value deposits, savings accounts.”

The bankers “who have joined us over the past seven years here in Switzerland have never worked for a bank in a positive rate environment,” he added.

The juxtaposition of beneficial rate hikes and damaging consumer and corporate distress has divided opinion on how European banks will fare after a decade in which their earnings have stagnated and Its stock prices have far underperformed its American peers.

You are viewing a snapshot of an interactive chart. This is likely because you are offline or because JavaScript is disabled in your browser.

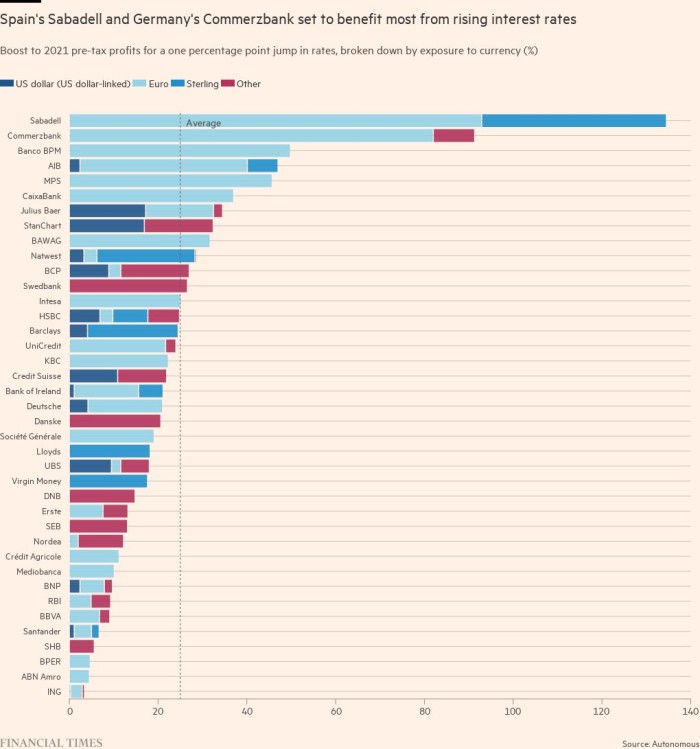

Many are optimistic for the first time in years. The rate hikes were hailed as a “game changer” for the sector by Morgan Stanley analyst Magdalena Stoklosa. Higher base rates mean higher profits as interest income (NII), a measure of the difference between what a bank pays for deposits and charges for loans, improves.

“We believe rate hikes in the eurozone are . . . the biggest structural catalyst for European banks,” Stoklosa said. She predicts the “cheap” sector is “52 percent upside” from its current depressed stock market valuation.

Those with large balance sheets and loan books benefit the most. HSBC, for example, has a global deposit surplus of $700 billion and has estimated that a 1 percentage point jump in rates would generate an additional $5 billion of annual NII, equivalent to one-tenth of $50 billion of last year’s income.

Lloyds Bank estimates that a one percentage point rise in base rate adds £675m to its earnings in the first year.

You are viewing a snapshot of an interactive chart. This is likely because you are offline or because JavaScript is disabled in your browser.

Rising rates and the resulting market volatility are also good for investment banks. Barclays, BNP Paribas and Deutsche Bank have generated billions in revenue through their large trading arms as client activity has increased.

On Thursday, Barclays said fixed income trading revenue rose 71 percent to £1.5 billion in the second quarter. Similarly, Deutsche Bank reported a 32% quarterly increase and Goldman Sachs posted a 55% gain in the same business earlier this month.

“If you’re an asset manager or a firm, a long-term rate trend means you have to rebalance your portfolio more often, which has generated significant revenue for us and the industry,” he said. Ram Nayak, co-head of investment banking at Deutsche.

This optimism of analysts and investors has not been seen for years. Hit by anemic profits, misconduct scandals and higher capital requirements, major European and UK banks have traded well below the book value of their assets. Few consistently achieve a return on equity of more than 10%, considered the minimum required by investors.

After the financial crisis, the region was slow to restructure and has lagged far behind Wall Street in investment banking. The lack of cash to invest in technology has left banks vulnerable to competition from fintech start-ups and big tech companies like Apple, Google and Amazon.

However, the end of years of ultra-low or negative rates “move their core franchise from a loss-making outlook to neutral,” Bank of America analyst Alastair Ryan said. Based on current projections for new hikes, BofA expects EU banks to generate a much-needed €17 billion in additional revenue each quarter a year from now.

Back to the 70s?

But even as optimism rises, a big question remains unanswered: How much of the interest rate windfall will be eaten up by higher loan losses. Consumers are facing an acute cost of living crisis and small businesses are beginning to struggle with lower spending and snowball inflation soon after global Covid-19 lockdowns.

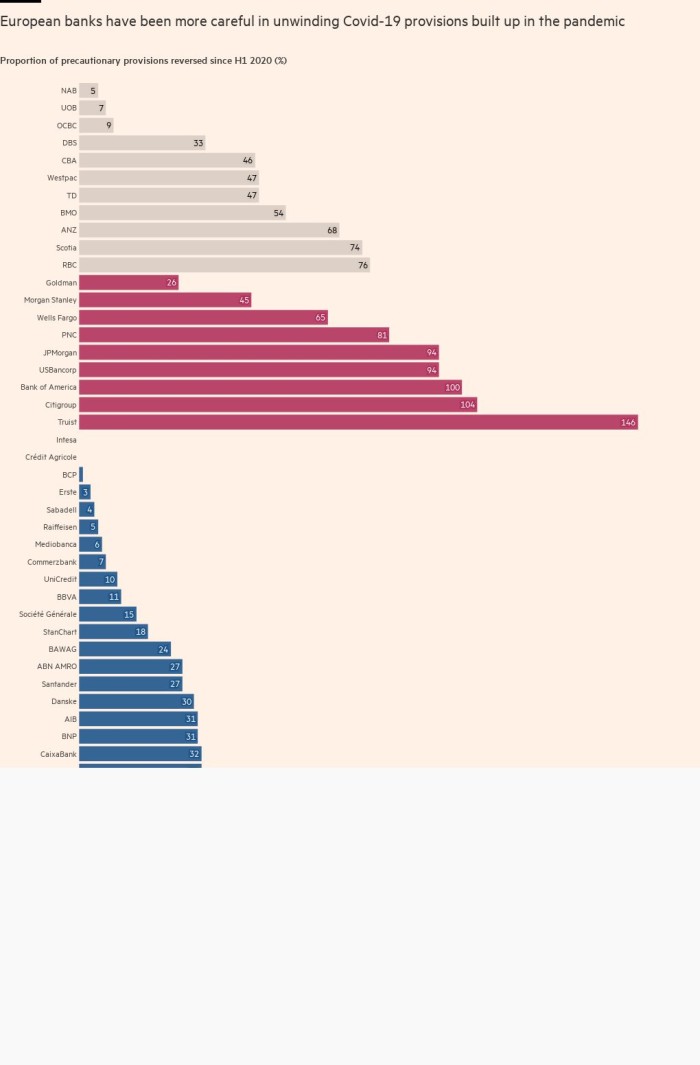

Some believe the sector can cope, as it did during the worst of the pandemic.

“Even with slower lending, we expect the recurring income benefit from higher interest rates to significantly outweigh the one-time impact of higher provisions,” said BofA’s Ryan.

Others are less optimistic.

“It is not easy to predict the impact of provisions and bankruptcies. The situation is like Covid; it’s completely new, we’ve never been through this since the 1970s,” said Jérôme Legras, head of research at investment firm Axiom. “When something is unpredictable, markets have a strong aversion to risk.”

A Capital Group portfolio manager led a €7bn sell-off in European bank stocks this year on fears the region’s economy had turned and lenders would suffer big losses and rising costs due to the inflation

Economic and political risks — such as in Italy, where the resignation of Prime Minister Mario Draghi has sparked a crisis that has spread to the government bond market and the banking system — have continued to rise.

“Recessions in both the US and Europe look increasingly likely. . .[and]History tells us that earnings in the European banking sector are typically down 50 percent,” said Autonomous analyst Stuart Graham.

“Current sentiment is overwhelmingly bearish,” he added. “Investors see a lot to worry about, mainly a recession driven by ‘Russia turns off the gas’, but also 1970s stagflation, bank taxes, etc., and few if any positive catalysts.”

However, there is little evidence of customer distress so far and much of the tens of billions in bad debt reserves linked to Covid-10 remain ready to absorb losses. European banks that have reported second-quarter results have, for the most part, beaten expectations, despite warnings of economic pain to come.

“The indicator that matters most for the quality of banking assets is global employment. We have to see how this plays out, but if labor markets continue to hold up as economists expect, credit quality should remain resilient,” Santander chief executive Ana Botín told the FT.

You are viewing a snapshot of an interactive chart. This is likely because you are offline or because JavaScript is disabled in your browser.

Barclays added no additional reserves to cover bad loans in the UK in the second quarter. Chief financial officer Anna Cross told the FT that “customers are acting in a very rational way”, for example paying off their credit card balances quickly.

“We’re seeing a real accumulation of savings by consumers and businesses and paying off unsecured debt, so they’re going into this environment in much better shape than before the pandemic,” he added.

Another UK bank executive said “we’re not yet seeing any signs of strain on our portfolio. The earliest is usually an increase in people making only minimum payments on credit cards, but while this increases a little, it’s not back to pre-pandemic levels.”

The BoE and ECB have already written to banks warning them not to be too harsh on distressed customers and the industry is keen not to lose the goodwill it built up during the Covid crisis.

There is also the possibility of more extraordinary government assistance for those struggling, as introduced during the pandemic, which will cushion banks’ exposure to insolvency.

“Most likely there will be subsidies to companies struggling with the energy crisis, guaranteed loans, etc.,” Axiom’s Legras said. “I think the reaction from the public sector will be helpful for the banks.”

Easy goals

However, a widespread fear among bank executives is that higher profits will attract new taxes. Spain has proposed an extraordinary tax of 4.8 percent on bank fees and interest, designed to recoup some of the benefits of higher rates.

When it was announced, it wiped billions off the valuations of the country’s five biggest lenders including Santander and BBVA. Hungary has levied its banks while Poland is putting a moratorium on mortgage payments to help struggling homeowners.

“Banks are easy targets and the prospect of even more taxes is terrifying for banks” [valuation] multiple,” said a hedge fund manager specializing in European finance. “Blaming the big corporations is always a tried-and-tested way in a recession to deflect from the government’s own policy failures.”

Bruno Le Maire, the French finance minister, told the FT in a recent interview that he has not ruled out unexpected taxes next year and that “the burden of inflation must be shared equally between the state and companies”.

The UK already has a bank rate and surcharge of 3 per cent on bank profits, recently reduced from 8 per cent, but at risk of being reinstated if the Treasury needs cash.

Regulators are also moving to cut another potential windfall related to tariffs.

The ECB is examining how it can prevent banks from making billions of euros in extra profits from its €2.2bn subsidized lending scheme, which was launched to prevent a credit crunch during the pandemic. Some analysts had estimated that lenders could make a collective €24 billion by re-depositing cheap debt with the central bank to benefit from higher current rates than when the loans were issued.

But while there is still much debate about the profitability of the European financial system, few are concerned about its solvency. Recent stress tests indicate that most lenders could withstand even extreme economic stress after being forced to build substantial capital buffers after the 2008 crisis.

Some even see surviving another crisis as an opportunity for banks to shake off the lingering negativity surrounding them.

“A ‘good recession’ could even be a long-term positive for the industry,” Graham said. “If European banks can withstand this with no worse than a 25-50 percent impact on earnings, no large capital increases, no blanket ban on payments and limited bank raids and financial repression, this could end some of the persistent . doubts harbored by many investors”.

“But that’s the beautiful thing about European banks: you can always find plenty to worry about.”

Additional reporting by Owen Walker and Siddharth Venkataramakrishnan

[ad_2]

Source link